Unearthing Forgotten History

Gary Price’s Passionate Pursuit

Gary Price, a self-described historian and subject matter expert, has dedicated decades to unearthing the rich, often overlooked history of Alabama folk pottery. What began as a mild interest, sparked by an inherited piece of pottery, evolved into a profound passion that led him to become a leading authority on these unique artistic and historical artifacts.

His journey has not only shed light on the obscure origins of valuable pottery pieces but also corrected historical inaccuracies and established the authenticity of works now housed in prestigious museums.

One Jug, A Lifelong Journey Begins

Price’s deep dive into Alabama folk pottery was ignited in the late 1980s when his mother left him an average piece of alkaline glaze pottery – “just a jug, you know, just the average piece,” said Price.

This seemingly simple inheritance piqued his interest, leading him to frequent estate auctions where he observed a mysterious buyer, a “picker” from Georgia, according to Price, systematically acquiring every piece of primitive pottery, furniture and quilts available. This realization that local historical items were leaving the area spurred Price’s initial curiosity into action, kindling his interest in hunting down the pottery shops themselves.

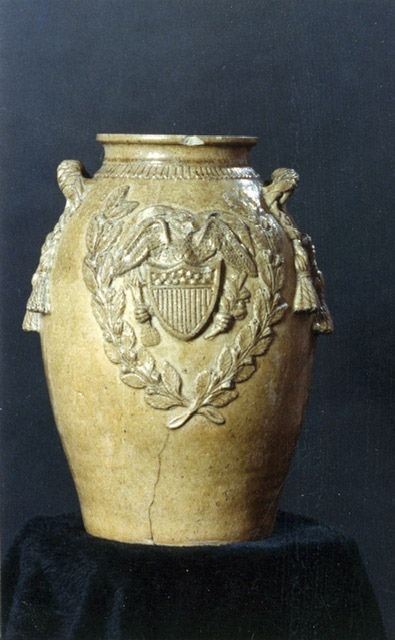

A jar made by John Lehman in early 1870’s at Jacob Eichelberger’s shop near Oxford, Alabama. Decorated with U.S. seal, winged angel and tassels.

“I thought to myself, ‘he’s buying primitive furniture, he’s buying primitive quilts. He was carrying it back into Georgia and selling it,” said Price.

Following Clues on Forgotten Roads

The quest to locate these long-lost pottery shops was no small feat.

Price and his wife, Martha, embarked on extensive explorations, often facing “roads [that] didn’t even exist anymore” and relying on fragmented information that “might take days just to get … to where it might be.” Their dedication sometimes meant navigating “railroad tracks for about 15 minutes and then back into the woods for another 10 minutes,” relying on subtle clues like family cemetery plots to pinpoint the proximity of historical shops.

Through persistent digging and exploring, the couple unearthed the physical evidence of these pottery operations, including “sherds” – fragments of pottery that were discarded as imperfect during the firing process.

These physical findings were crucial for identifying pots. As Price notes, if they [Price and his wife] had “never done this, Georgia would have claimed that work was done over there,” underscoring the importance of the couples’ work in maintaining authenticity.

Price’s own book, authored in 2022 and his contribution to the 2006 “Alabama Folk Pottery Book,” further solidified his expertise and the understanding of this regional art.

One side of the vase has a portrait of George Washington and a banner held by eagle. The banner reads, “Hurrah for Washington”. The other side has a portrait of Thomas Jefferson with a banner held by an eagle, reading “ Hurrah for Jefferson”.

The Entrepreneur Behind the Clay

Central to the story of these remarkable pottery pieces are two key figures: Jacob Eichelberger and John Lehman.

Eichelberger, an entrepreneur, arrived around 1850 from Hanover, Pennsylvania, in the Bacon Level community of Randolph County, Alabama. He owned a grist mill, a pottery shop and “a few slaves,” said Price.

After the Civil War, Eichelberger faced public disapproval due to his status as a former slave owner.

In an effort to rehabilitate his image and reestablish himself as a legitimate businessman, he navigated considerable bureaucratic red tape. This push for public redemption became the driving force behind the creation of his highly decorated pottery pieces — an attempt to present himself in a more favorable light and align with Union sympathies.

In 1869, he moved 50 miles north of Bacon Level to Oxford, where he established another pottery shop.

The Craftsman Behind the Vision

Lehman, a German-trained potter, also arrived in the Bacon Level community at roughly the same time as Eichelberger. Lehman was already a skilled potter when he came to the area and was the artisan responsible for crafting the elaborate pieces commissioned by Eichelberger.

When Eichelberger relocated to Oxford, Lehman followed, continuing to create these distinctive works. The diligent research of Price and his wife was pivotal in correctly attributing many of these pieces. They located Lehman in the 1860 census in the Bacon Level community of Randolph County, Alabama, and uncovered evidence of his decorative work on a friend’s property in Oxford. While Lehman’s signed, utilitarian pieces may not be as visually elaborate as his decorative ones, they are highly prized today due to their extreme rarity.

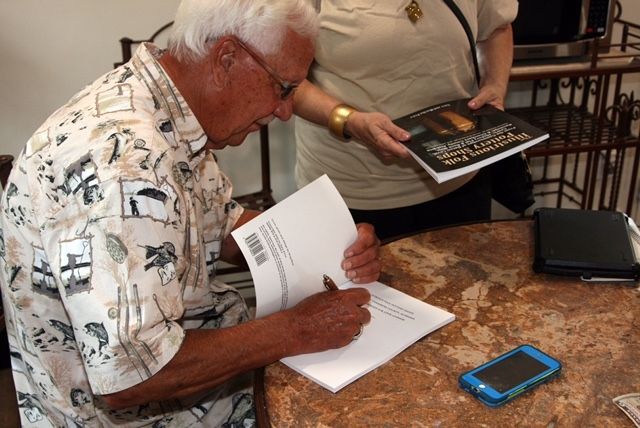

Gary Price signing a copy of the book he co-wrote with his wife Martha, The Illustrious Folk Pottery Shops.

Patriotic Themes in Clay and Glaze

Among the most significant discoveries are several highly decorated pieces that exemplify the unique collaboration between Eichelberger’s vision and Lehman’s craftsmanship.

One notable jar features the “Hero of Washington” and “Hero of Jefferson” inscribed on its sides, accompanied by “facial[s]” of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Adorned with ”laurel decoration and flowers, this piece would have been made right after the Civil War, according to Price, reflecting Eichelberger’s attempt to portray himself in a more favorable light by associating with American patriotic themes.

From Trash Cans to Treasured Relics

Another remarkable piece features the U.S. seal on one side and a winged angel on the other side. These pieces are not only aesthetically significant but also command high values. The George Washington/Thomas Jefferson jar, for instance, “was found years ago in a junk shop being used for a trash can,” said Price.

“Eventually it entered major collections and was acquired by the Birmingham Museum of Art for $82,000.”

Similarly, a “figural jug,discovered”in a junk stop in the 1960s for $12, was later identified as a John Lehman piece by the owner’s granddaughter and sold to the Birmingham Museum for an astonishing $100,000.

The High Museum in Atlanta has one of the figural jugs as well. The distinctive alkaline ash glaze — a homemade blend that used wood ashes — is a hallmark of these remarkable works, transforming humble clay into what Price calls “great works of art.”

The piece featuring the winged angel on one side and the U.S. seal on the other, for instance, is currently being held in a private collection.

Price’s expertise extends beyond discovery and historical attribution; it encompasses a deep understanding of the market and the inherent value of these historical works of art. He learned to identify pieces that others would not be able to. This allowed him to acquire valuable items for little cost, often before their provenance was widely known.

For example, in 1993, Price bought a piece for $100 simply because he “knew it was beautiful.” Today, that same piece is estimated to be “worth a few thousand” dollars. His research also corrected longstanding misattributions, including a book written in Georgia probably in the 1980s that incorrectly claimed a particular piece was made by a Georgia potter.

As Price explained, “Nobody knew at the time,” but his discovery of John Lehman in the 1860 Alabama census helped set the record straight.

The Vulcan statue is the largest cast iron statue in the world, and is the city symbol of Birmingham, Alabama, United States, reflecting its roots in the iron and steel industry. The 56-foot tall statue depicts the Roman god Vulcan, god of the fire and forge, with ironworking equipment.

Museums Recognize Southern Clay Legacy

The significance of these works is reflected in their inclusion in institutions like the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Founded in 1951, the museum holds “a diverse collection of more than 29,000 paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings and decorative arts dating from ancient to modern times.” Its mission — to “spark the creativity, imagination and liveliness of Birmingham by connecting all of its people to the experience, meaning and joy of art” — aligns with the acquisition of these historically rich folk pottery pieces, which showcase the region’s artistic heritage.

Ultimately, Gary Price’s “interesting hobby” is far more than a pastime. It is a serious historical pursuit fueled by interest and passion, a desire to preserve local history and an appreciation for the challenge of uncovering the unknown. Through tireless research, fieldwork and collecting, Price has become a true subject matter expert and a key figure in telling the authentic story of Alabama’s folk pottery tradition — ensuring the legacies of craftsmen like Lehman and entrepreneurs like Eichelberger are properly honored and remembered.

Tags:Features

Acreage Life is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.