What the Hay? Stocking the hay barn with your senses

As many local hay farmers are preparing to do their final cutting or are getting their last round of hay into the barn, it’s a good time for you to stock up on hay ahead of winter. Depending upon where you live, your hay source may vary from the farmer up the road to a commercial shipper from several states away.

Here in central Kentucky, we’re fortunate to have a climate that allows for decent hay production during the summer and fall, so I’m accustomed to buying my hay in square bales from a local farmer. If you can get good quality hay this way, I think locally-sourced stuff is best; not only is it often the most affordable option, it’s going to be the most similar to the pasture your horse grazes on through the year. Horses, as we know, love consistency. In some places like the West and Southwestern states however, there isn’t enough pasture or local hay supply and you’ll have to rely on buying from a larger commercial operation.

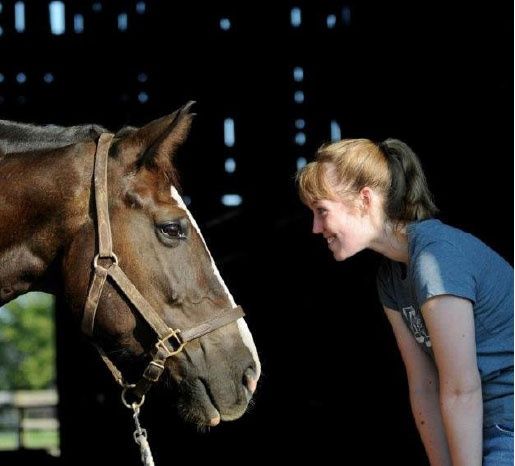

Wherever you’re getting your hay from, you can use your senses to decide whether you’re comfortable feeding a given sampling to your horse. If you find a hay supplier you’re happy with, it’s a good idea to buy hay in as large a batch as possible to minimize the number of times your horse will be asked to adjust to a new group with slightly different contents.

Sight

The best hay will be free of sticks or foreign material, and will have a high proportion of leaves in the bale. The greener the bale, the younger and more tender the hay will be, and the richer it will be in nutrients for the horse.

Legume hays like alfalfa should not have flowers in them, since that will indicate greater maturity.

Shake loose a couple of handfuls of hay to see if excessive dust comes up. Dusty hay is not only likely to be of a reduced quality, but could also irritate your horse’s respiratory system.

Feel

Check for maturity by getting your hands into a bale and feeling how fine or thick the stems are. Thicker, stemmier hay tends to be lower quality and a later maturity than fine, leaf-plenty hay.

Also, if you reach into a stack of hay and notice it’s warm or hot, which could indicate it had a high moisture content when baled. As moisture trapped inside the bales continues to heat, the risk for internal combustion from a group of stacked bales increases. If you’re looking to check the temperature on your own bales or on a test group, beware of internal temperatures 150℉. and above.

Smell

Your nose is the best detector of mold or mildew in a batch of hay. Feeding hay tainted by either of these puts horses at risk of colic.

Your senses will tell you whether hay is sufficiently safe or of adequate quality to feed to horses, but you can’t learn everything from them. A chemical analysis is the only way to really know how much of each type of nutrient your horse will get.

How it’s measured

If your hay provider is able to provide a chemical analysis, the most important numbers to pay attention to are the crude protein, neutral detergent fiber, and total digestible nutrients.

- Crude Protein is an estimate is based on total nitrogen content and this decreases with maturity.

- Neutral Detergent Fiber (NEF) represents fiber from cellulose and lignin, so it represents cell walls that are only partially digestible for the horse. The higher NDF, the less the horse will have to eat before becoming full.

- Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN) includes the total amount of digestible protein, starch, sugar, fiber, and fat. Grass hay tends to have the highest percentage of NDF, while alfalfa has higher average numbers for crude protein and TDN, according to the University of New Hampshire’s cooperative extension service.

Heat In Hay Bales

One of the biggest things you can do to reduce your risk of a barn fire is to make sure your hay is stored safely. Hay baled with too much moisture will generate heat, and if it’s stacked with poor airflow, that heat is compounded.

Experts suggest bales with internal temps between 150℉. and 160℉. be disassembled from their stacks and repositioned to allow more airflow through individual bales and across the pile.

Remember that shielding hay from rain by putting it in a totally enclosed space also reduces airflow necessary to reduce heat. Bales in this danger zone of heat should be checked every two hours to ensure temperature isn’t escalating.

Bales with an internal temp above 175℉. are extremely likely to have hot spots. Air flow should be minimized around these and they are likely to ignite imminently. If you get a reading this high, alert your fire department.

Tags:Horse Sense

Acreage Life is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.