Positive-ly Closing the Waste Loop

Dairy, food waste turned into rich compost

Eric Paris of Tamarlane Farm, an organic dairy in northeastern Vermont, has been closing the loop on his farm by composting farm waste and community food scraps (about 12 tons per week) to create a valuable fertility source for his farm fields.

Tamarlane Farm is both the production and receiving end of his two family-owned businesses, the Freighthouse Market and Cafe, and the Mosaic restaurant (thelyndonfreighthouse.com and mosaicfood.com).

“Our farm is a certified organic dairy, beef and vegetable operation. We've been certified organic since 2003, we're members of CROPP Cooperative and our milk from our certified organic holsteins is marketed under the Organic Valley Grass Milk brand,” Paris tells us.

Isn’t there a better way?

Back in 2005, Paris began accepting food scraps, wood chips, and other biomass to mix with scraped dairy manure to make compost. For years, he handled the compost in a traditional manner: building windrows and using equipment to turn piles for aeration—regularly folding air into the pile helps break down components into compost. A portion of his compost was sold to local gardeners and landscapers.

Then in 2014 Eric received a grant from Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) to explore a positive aeration system for the compost pile.

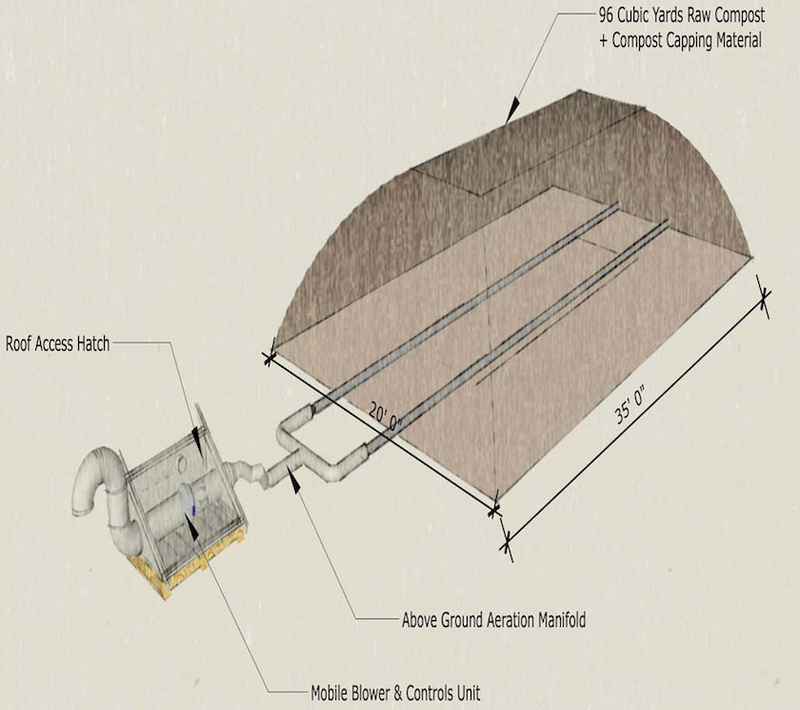

His Farmer Grant project sought to determine whether a low-cost Aerated Static Pile (ASP) system would improve the efficiency of the farm’s composting program as compared to the typical composting method he was using.

Paris was specifically interested in learning if an ASP system–which uses a fan and ductwork to force air into the piles without turning them–would reduce composting time, space needs, and labor hours.

Comparing ASP systems available, the system they trialed cost about $1,000 in materials, making this an affordable DIY-style option for his composting operation as well as for other farms of a similar scale to Tamarlane Farm.

Hotter faster but…

Through this research, Paris found that the ASP system trialed was able to achieve temperature requirements (as defined by the National Organic Program) for the compost material in 3 days versus 15 days with the turned windrow system. A bonus, he found the system used only about one-third of the space needed for the turned windrow method.

Labor savings were inconclusive; in fact, Paris noted that the ASP system’s aeration schedule needed to be monitored more frequently and adjusted to prevent the piles from overheating or drying out. However, he believed that with more experimentation, the ASP system would be a labor saver.

The better way

So, with the reduced space requirement, and faster rise-to-temperature, ASP held much promise for Tamarlane Farm—but it just required some finesse since overheating the piles could be a problem.

In 2020, Paris began working with Agrilab Technologies, Inc. (agrilabtech.com) to design a two-stage compost aeration system. Grant and cost-sharing funds from the Vermont Clean Energy Development fund and Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and markets and others helped fund the project.

Last summer, work began with trenching, grading, and construction of a compost aeration and heat recovery (CAHR) unit. Large HDPE aeration pipes circulate air at the base of the compost pad, and through the CAHR unit, excess heat is “siphoned off” to warm Tamarlane Farm’s greenhouse and garage.

By the end of the year, Tamarlane Farm’s composting proved to overcome overheating issues, plus set up a needed off-grid heat source for important farm buildings.

Thanks to Eric Paris, Agrilab Technologies, Inc. and Northeast SARE for information to produce this article.

Tags:Weekend Farmer

Acreage Life is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.